Darwin's Abominable Mystery: the Abundant and Amazingly Successful Angiosperm that so graces our planet in its myriad expressions of beauty....

_resized.jpg) |

| Lemon Flowers |

Spring flowers in my Northern California garden before the dry Mediterranean summer takes over.

|

| Nasturtiums |

Angiosperms, flowering plants presented a bit of a conundrum to Charles Darwin and generations of biologists after him. How did angiosperms radiate and diversify with such dizzying and effortless array into the myriad 300,000 forms that may be found within the covers of any Botanical Encyclopedia and which are sprinkled throughout parks and gardens of the world? A trip to any art gallery in the world will confirm not only the impact of flowers on culture but to our sense of wellbeing and romance as well. Even a little white daisy poking its head through a crack in a wall brings with it a certain ineffable beauty.

The angiosperms are pollinated plants producing flowers and fruit that diverged from gymnosperms. Although angiosperm-like fossil pollen has been found that dates to the Middle Triassic in Germany Hochhuli, P.A. and Feist-Burkhardt, S. (2013) , the first small flowering plants became widespread within 120 MYA, replacing conifers (gymnosperms) as the dominant tree type around 60-100 MYA. Davies, T. J. et al. (2004)

As in the graph below, 125 MYA gymnosperms which include cycads and conifers were the major plant groups. Angiosperms were rather small plants, growing alongside stream or even dry salty places where their thick leaves helped conserve water. Then between 125 to 65 MYA, flowering plants exploded from a small minority into 80% of all plants. According to a theory of Berendse and Scheffer (2009), the reason has to do with soil quality. Although Gymnosperms flourished in poor soils, they did not improve soil quality. Angiosperm litter replenished soils however, creating a positive feedback between improved soil fertility and angiosperm expansion.

From Cox and Moore, Biogeography (2010)

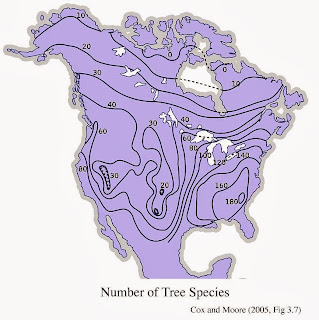

So returning to the question of refugia, how does the topic of angiosperms relate? Well, indirectly there are some interesting contrasts to highlight. Note the map below showing the richness of tree species on a Latitudinal Diversity Gradient (LDG).

From Cox and Moore Biogeography (2010)

There are 644 tree species in Yasuni National Park, Ecuador -

There are none at the North Pole.

There is a consistent latitidinal decline in life forms moving north

Simliar trends may be seen in mammals and birds. Much greater diversity may be found closer to the equator. It appears that the sun, warmth and moisture are kind to life on earth and that the cold, dry climes of far Northern Hemisphere are limiting factors for survival. Note however that a correlation betwen latitude and evolution has not been fully resolved. Mittelbach, G.G. et al. (2007)

However, the following map which showing global diversity suggests a limiting trend of the Northern Hemisphere Pleistocene glaciation cycles.

Barthlott, Klier, Rafigpoor, Kreft, Kuper, Mutke & Nees Institut for Plant Biodiversity (2004)

CLICK ON MAP TO ENLARGE

Finally, gymnosperms - the conifers - largely outcompeted by the dazzling success of angiosperms adapted to harsher climates with needle-like leaves and structural cone shapes that did not facilitate much snow accumulation.

Flowers are found at alpine locations but they tend usually to be small, hardy plants, such as Rosebay Willowherb (Epilobium Angustifolium) below.

This hardy little flower is one of the first to appear after a glacier retreats, such as this image from Glacier Bay in Alaska.

In a warming more humid world, perhaps this post might offer a ray of hope.......

Hi Michele, this is an interesting post about angiosperms and distribution of biodiversity. Interestingly, I noticed that flowers at mid-latitudes generally have more vibrant colours (like the pictures in your posts) compared to those near the equator. Having read that biodiversity is richer at the equator, I wonder if the vibrant colours could be an adaptation measure of mid-latitudes angiosperms to promote enhanced pollination, while flowering plants in the equator having a more conducive environment may find less need to do so.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Joon for your interest. I'm attempting to respond to your observation regarding flower hues but so far only confirm that tropical passerine birds are noticeably more colorful than birds at higher latitudes. I think larger flower heads might be a feature of angiosperms at lower, wetter and warmer latitudes but can find nothing definitive regarding flower colours and LGD thus far. Allso in mid-latitudes zonal climatic influences are important for horticulture.

ReplyDeletePalaeobotany is one of my pet fascinations. Given how small the number of plant species is compared to animal, it's surprising to me how many living fossils are around today. Cycads, cycadoids, ferns, ginkgos, conifers... I used to watch "Walking with Dinosaurs", and was amazed more by the alienness of the plant surroundings than the CGI Allosaurus.

ReplyDeleteAnd here's another thing: I can't remember where, but the evolution of flowers has been linked to fruit and thus a big, colourful new food source that many species depend on, including humans. It's been argued that humans, intelligent life, evolved because of the angiosperm explosion.

Thanks so much for your interest. It only makes sense that humans evolution was greatly assisted by the angiosperm explosion - all those vitamins and nutrients! Another interesting observation though is that man emerged about 1.5 MYA, possibly concurrent with the advent of grasslands in Africa.

ReplyDeleteThanks for this interesting post about angiosperms - I enjoyed seeing the lovely photos from your California garden. You spoke briefly about altitudinal gradients of angiosperm diversity with the alpine Alaskan flower. How does the presence of mountains or highlands affect the latitudinal gradient of angiosperm diversity?

ReplyDeleteThanks, Katherine for your question....the environmental lapse rate - increasing cold with altitude up a mountain side is similar to moving northward on a latitudinal gradient. Alexander von Humboldt, called the father of biogeography first documented this in the early 19th century when he climbed Mt. Chimborazo, Ecuador, noting a change in plant species with altitude.

ReplyDeleteThanks for the info Michele! Looking forward to your next posts.

ReplyDeleteCheers,

Katherine